From muse to murderer: how France fell out of love with absinthe

The story of absinthe begins and ends with two Frenchmen in Switzerland. The first was a doctor who created a new spirit alcohol with an unusual green colour that would go on to be a hugely popular drink in France, lauded by poets and artists, synonymous with the good times of the Belle Époque. The second was a labourer who drank this same alcohol one day at lunch then returned home where he shot and killed his pregnant wife and their two children. It was a crime so shocking that it brought about the ban of absinthe in much of Europe and the United States.

In the hundred years of its rise and fall, absinthe was credited with and blamed for many things: a cure for disease, an artist’s muse, the degeneracy of a nation and even provoking a murder. But which, if any, of these is true?

A medical elixir

It was in the town of Couvet, Switzerland in 1792 that Dr Pierre Ordinaire created his new herbal drink by distilling three herbs: green anise, fennel and wormwood. This Latin name for this latter ingredient (Artemisia absinthium) gave the drink its name: absinthe. This medicinal beverage had a distinct herbal flavour, a strong taste of aniseed that would be familiar to anyone who has tried modern day ouzo or pastis. Another feature of Dr Ordinaire’s drink was its striking green colour. This was caused by the herbs’ chlorophyll, brought out during the maceration process where the leaves break down and leak their colour into the brew.

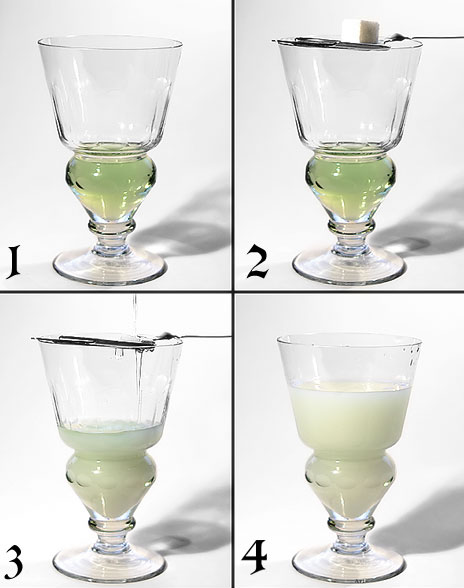

One final factor that set absinthe apart was its high alcohol content. At around 70% ABV, it was was considerably stronger than other spirits like gin or whisky, which typically are 40% proof. To drink absinthe, therefore, it was necessary to dilute it with water, at a ratio of about 4:1. Adding water to the clear green liquid turns it pale and cloudy, an opalescence that would later come to be referred to as la fée verte (the green fairy).

Dr Ordinaire’s patented medicine enjoyed modest success from the beginning. Within five years the recipe had been bought by Pernod Fils who began manufacturing in Switzerland, then in France. But the real boost to absinthe’s popularity came when the French army began using it as a preventative for malaria. The 1830 invasion of Algeria meant great numbers of troops were stationed in this hot climate and being given regular doses of absinthe. The soldiers’ thirst for absinthe didn’t diminish on their return to France, and the drink soon was being sold in bars and cafés across the country. Absinthe had made an important transition from medicine to beverage and was now well on its way to becoming France’s favourite drink.

The apéritif

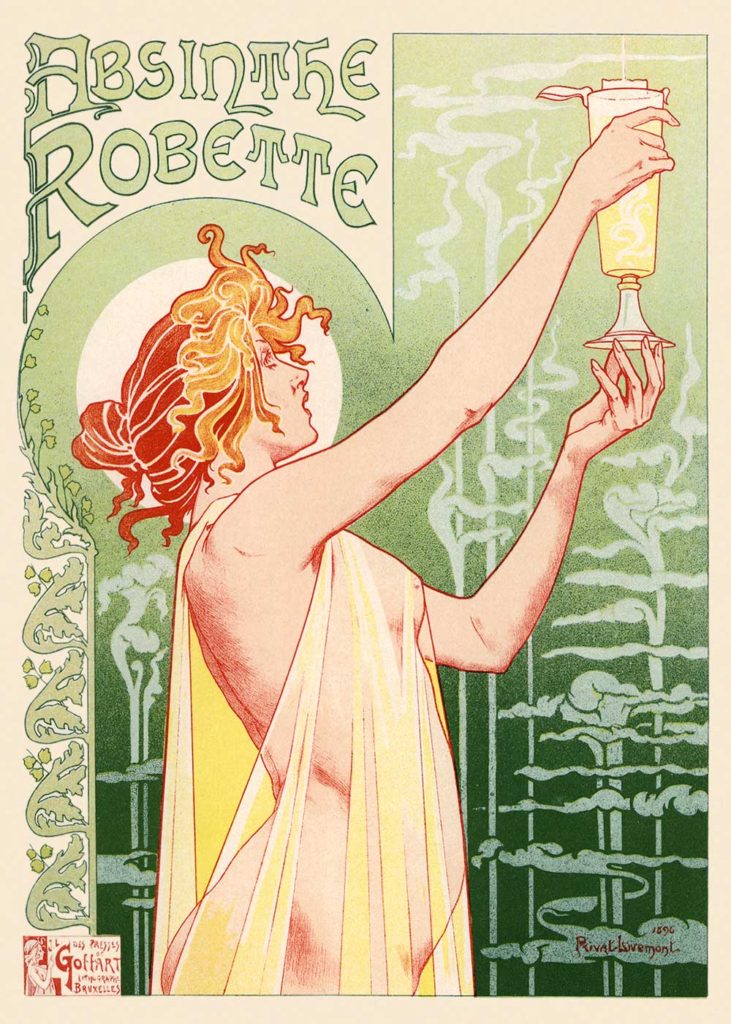

Five o’clock, in the second part of the nineteenth century, was known as l’heure verte (the green hour). Terrace tables across the country were filled with smartly dressed people enjoying their little glasses of green liquid. Part of absinthe’s appeal was the ritual of its preparation: one that required props and a degree of patience. The method employed in France at the height of absinthe’s popularity involved resting a slotted spoon on the rim of a glass containing one part of absinthe, placing a sugar cube on the spoon, and pouring a steady trickle of icy water over the sugar, dissolving it into the glass. In time, special water fountains with multiple spouts were designed which allowed several drinks to be prepared at once.

In the early days of its success, absinthe was a drink of quality with a price to match. But demand for this fashionable apéritif grew and it began to be produced in mass quantities. The price of absinthe dropped sharply so that, by the 1880s, people of all social classes were able to drink it. At the height of its popularity, absinthe accounted for 90% of all apéritifs drunk in France with 36 million litres being produced a year. This affordability came at a price, however, with a reduction in the quality that, in some cases, led to cheaper and dangerous substitutions being made during production, for example, toxic copper salts being used to give an artificial green colour instead of carrying out a second distillation.

Artist’s muse

During the Belle Époque, absinthe was the drink of choice of a great many artists, writers and poets. Vincent van Gogh, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Marcel Proust, Charles Baudelaire and Émile Zola were known to be fans of la fée verte. The poet Arthur Rimbaud used absinthe, along with hash and opium, as an artistic tool, a means of tapping into otherwise inaccessible creative parts of his mind. It was this mind expanding property of absinthe that appealed to many. A friend of Oscar Wilde’s recorded his description of an absinthe-induced hallucination.

Three nights I sat up all night drinking absinthe, and thinking that I was singularly clear-headed and sane. The waiter came in and began watering the sawdust. The most wonderful flowers, tulips, lilies and roses, sprang up, and made a garden in the cafe. “Don’t you see them?” I said to him. “Mais non, monsieur, il n’y a rien.”

Oscar Wilde, via Ada Leverson

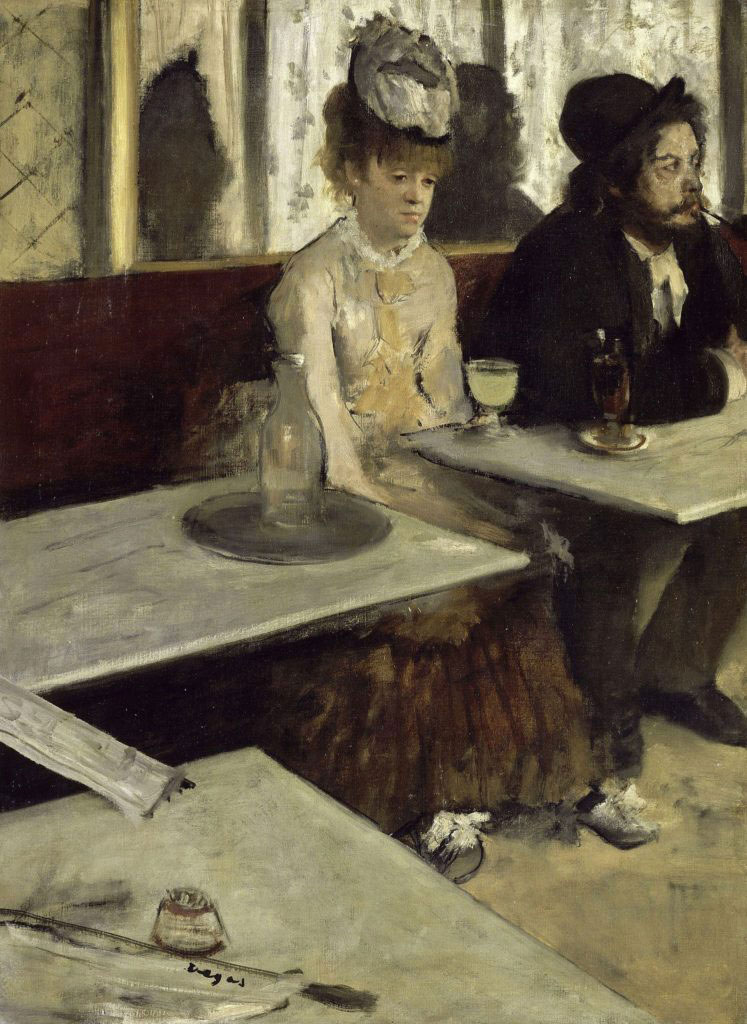

Absinthe and absinthe drinkers were a frequent source of inspiration for artists. Edgar Dégas’ painting L’Absinthe depicts a couple in a bar, a glass of absinthe prominently before the woman, both staring blankly into space. The degradation of the pair shocked critics who called the painting “ugly and disgusting”.

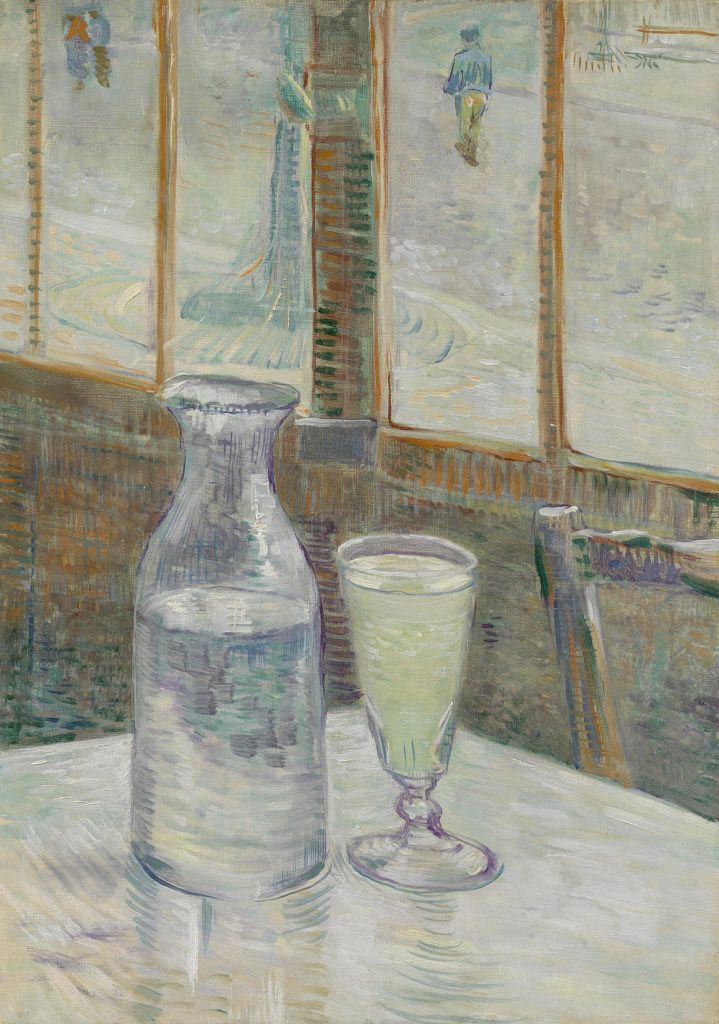

The ugliness of alcohol addiction was worlds apart from this still life by Vincent van Gogh, who shows the beauty of absinthe itself. In Café table with absinthe, van Gogh shows us the world from his perspective at his table in a Paris café, his drink before him on a zinc-topped table, the passersby on the boulevard providing entertainment for the idle observer. The light from outside spills through the large window, bouncing off the table and glassware, revealing the opalescence of the pale green drink. Van Gogh’s bright colours are a marked contrast to Dégas’ murky palette, suggesting an appreciation of absinthe that wasn’t borne out by reality.

The artist’s troubled mental state is well documented, even if its cause is not. What is known is that van Gogh often drank absinthe to excess, which has since lead to speculation as to the part it may have played on his physical and mental health. There were even questions as to whether an ingredient found in absinthe was responsible for van Gogh’s bouts of madness – the extreme acts of violence that saw him on one occasion cutting off his own ear. A leading French psychiatrist, Dr Valentin Magnan, had been studying absinthe drinkers and had come to some disturbing conclusions that would have serious repercussions for the future of absinthe.

Poison

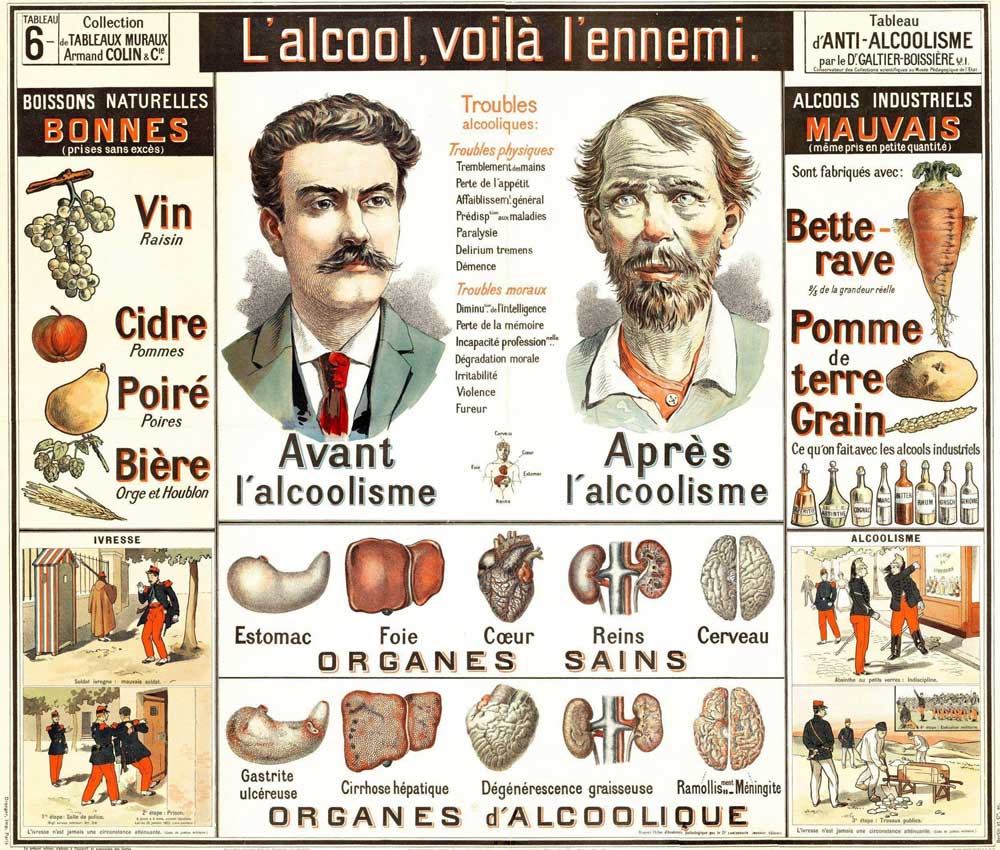

Dr Magnan believed that French culture was in decline. Looking at French society in the 1870s, he saw evidence of degeneracy in the population – an inherited genetic decline from one generation to the next – and attributed this to the changed drinking habits in France. Wine – the traditional drink of the French – was being replaced by an extremely strong spirit in all social classes, by women as well as men. The concept of alcoholism was in its infancy but the link between excessive consumption of alcohol and poor health, even criminality, was beginning to be drawn.

In his laboratory, Dr Magnan sought to prove that absinthe in particular was slowly poisoning the country. Intoxication from absinthe was different, more dangerous, than from other alcohols. The reason for his, he found, was the presence of wormwood in absinthe. Guinea pigs experienced epileptic convulsions when he gave them essence of wormwood – something that did not happen when they were given alcohol. This, Magnan concluded, was why drinkers experienced states of delirium – hallucinations – when they drank absinthe. In his studies, he named this the “absinthe effect” – a term that would later be used in a court of law to argue that absinthe could induce people to commit horrendous acts.

At the time of his researches, however, the response from the public was mixed. Certain, like Toulouse-Lautrec, were even encouraged to drink more given this “scientific proof” of absinthe’s mind-altering capacities. But others, like the Anti-Alcoholic League of France, took note and used it to strengthen their case against absinthe, a drink they already believed responsible for causing tuberculosis, epilepsy, insanity and paralysis. While the Anti-Alcoholic League enjoyed increasing support from the Catholic church, unions, doctors and the press, the public turned a deaf ear, continuing to enjoy absinthe in vast quantities. It would take an incident outside of France, one that inflamed the public’s emotions, for the tide to finally turn against absinthe.

The murderer

On the afternoon of 28 August 1905, Jean Lanfray, a French labourer living in Switzerland, returned home after lunch with his father. The pair had been drinking heavily and had eaten only a sandwich. At home, Lanfray got into an argument with his pregnant wife after she refused to clean his shoes. In retaliation, he took his gun and shot her dead. He then turned the gun on their two daughters, Blanche (2) and Rose (4) before aiming the gun at his own head and pulling the trigger.

He missed. Instead of killing him, Lanfray’s bullet hit his jawbone. By February of the following year, he had recovered and was standing trial for the triple murder. The court heard how, on the day of the murders, he had drunk seven glasses of wine, six glasses of cognac, two crème de menthes, a coffee with brandy and two glasses of absinthe. His defence attorney invoked Dr Magnan’s “absinthe effect”, arguing that Lanfray’s actions were “a classic case of absinthe madness”. In short, absinthe was responsible for the murders, not the man. The jury disagreed. Lanfray was found guilty and was sentenced to 30 years’ imprisonment. Three days after the verdict, Lanfray hanged himself in his cell.

While the “absinthe effect” strategy may have been unsuccessful in court, it struck a chord outside. News of the murders had been met with outrage from the public, who had difficulty believing that a man could be capable of killing his young family. The Swiss and French public alike followed reports of the trial with great interest, taking in the defence’s accusations that absinthe led him to commit such a vile act. People were looking for an explanation, something to blame, and absinthe fit the bill. Rightly or wrongly, it was the publicity that the temperance movement needed.

The outlaw

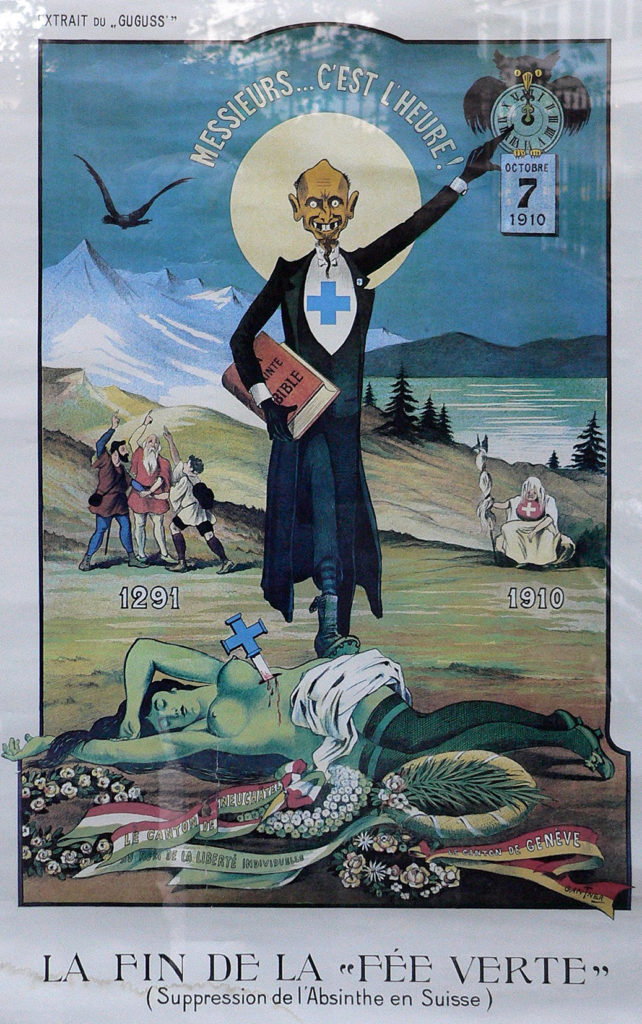

Support grew for bans on the sale of absinthe. In Switzerland, a referendum on the subject was held in 1908 with voters in favour of the ban; it was written into law in 1910.

By then other countries had taken similar steps: Belgium, the Netherlands, Brazil and the United States all introduced similar legislation. France held out longer. More absinthe was still drunk in the drink’s homeland than anywhere else but this was no longer the frivolous France of the Belle Époque, it was a nation fighting a war on its own soil. With cries of “Tous pour le vin, contre l’absinthe” (“All for wine against absinthe”) the Anti-Alcoholic League had its way. Absinthe was banned in France in 1915.

The trendy drink

One country that never tried to ban absinthe was the United Kingdom – it was never a popular drink, so there was no need. But, curiously enough, Britain was one of the instigators of absinthe’s revival. In the 1990s, British drinking culture was in full swing and bars began importing absinthe as a novelty from the Czech Republic where it was still manufactured. A trend was born with more and more people wanting to try the notorious drink. But was it safe?

Much more is known about the make up of absinthe nowadays. We know that it is not, in fact, hallucinogenic. Dr Magnan’s conclusions about absinthe’s toxicity were faulty because he exposed his lab animals to far greater levels of thujone (the chemical present in wormwood suspected to cause convulsions) than the trace amounts found in absinthe at the time. The real risk from absinthe – outwith those associated with any alcohol consumption – was in drinking the cheap versions with their substituted ingredients.

The safety of absinthe is no longer in question which is why, since 2011 in France, it is available to buy in shops and bars once again. It’s true that pastis – a less alcoholic cousin of absinthe without the wormwood – has largely replaced absinthe in France as the aniseed drink of choice. But absinthe, and her associations with the great artists of the Belle Époque, has a mystique that no other drink can hope to match. The green fairy flies again.

Sources

https://www.wikiwand.com/en/Absinthe

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Absinthe_(spiritueux)

https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20140109-absinthe-a-literary-muse

Al McKinnon, Calgary Canada

Thank you again, Jackie!

It’s only noon here as I type this, but there will be a Sazerac tonight and Death in the Afternoon on New Year’s Eve! … Al

admin

Excellent choice! I’m tempted to try a Hemingway special on NYE myself. Good idea!